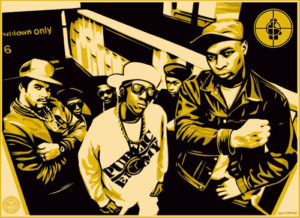

It may seem like hyperbole to say that a music act can alter one’s worldview in a significant way, but anyone who knows me knows that music is an incredibly important, often powerful part of my life – and “powerful” is as apt a term as any for what Public Enemy has to offer.

After all, Public Enemy changed the way I see the world.

After all, Public Enemy changed the way I see the world.

For those only passingly familiar with them, Public Enemy is a now legendary hip hop group best known for songs like Fight the Power, Bring the Noise, and 911 Is a Joke.

They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012, making them a crossover powerhouse who may not have burned up the charts – they’ve never had a top 20 hit and even their three best selling records failed to tear up the mainstream charts – but who, like The Velvet Underground, had a huge influence on everyone who heard them.

I was one of those people.

Public Enemy formed in Long Island back in 1982, quickly establishing a reputation in New York as an uncompromising act unlike anything that we’d see before. They came to the wider public’s attention with their 1987 debut, Yo! Bum Rush The Show. Heavily influenced by Run-DMC in sound but taking the lyrical game to new places, the album put them on the mainstream hip-hop radar and arguably ushered in a five-year stretch of rap that was focused on social consciousness, knowledge, and political activism. You could argue that without PE, we wouldn’t have had KRS-One and Boogie Down Productions, the underrated Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, Arrested Development, and even the street consciousness of NWA.

Public Enemy wasn’t the first rap act to deal with the uncomfortable truths of life in America as an urban black, of course. That had been a hallmark of rap from the very start, from the legendary “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five – “It’s like a jungle sometimes / It makes me wonder how I keep from goin’ under” – to Run DMC’s “Hard Times” (actually a Kurt Blow cover) and many others. It’s a genre that had embraced truth-telling and storytelling just as strongly as it embraced party jams and larger than life boasts.

But when Public Enemy’s second album, It Takes A Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back, dropped in 1988, the game changed. This was a loud, dense, challenging record that came at listeners with fury both sonic and lyrical. It was a whirlwind of sound and words. Unpeeling Chuck D’s reference-laden wordplay could be difficult on a good day, but when set amid the blare of layered horns, sirens, and machine-gun beats? It was Earth-shattering stuff.

“The power is bold, the rhymes politically cold”

I can still remember the first time I saw and heard them. I grew up in a small New Jersey town of about 3,000 people, a town out in the sticks that was partially diverse only because the adjacent military base meant families of color lived there a few years at a time when stationed at the base. Military families aside, you could literally count the number of local black families in town on one hand (and two of them lived on my block).

The year was 1988, and I had just walked into a friend’s house. MTV was on. I don’t recall if it was Yo! MTV Raps, which had just launched that year, or just general music videos, but what I do remember was that what I saw blew my mind. Faux news broadcasts, black men in paramilitary garb, music with sampled horns that sounded like something from a dystopian hell, and in-your-face lyrics that shone a light onto a world I was unfamiliar with it.

It was this video for “Night of the Living Baseheads:”

Oh, we were familiar with the crack epidemic by then. It was all over the media, you couldn’t escape it, but what did some kid from some small New Jersey town really know about it? I knew how it was presented on the news – the impression I got was that inner city black communities were just vast crack dens and no one really cared about that – but I sure as hell didn’t know what people actually impacted by the epidemic thought or felt.

So here I am, watching angry young black men talk about how frustrated they were at seeing blacks victimized by other blacks and the toll it all took on their community.

This didn’t fit the narrative I saw on the nightly news. It didn’t fit the narrative I had always heard. ‘Blacks screw up their own communities,’ was the general consensus, ‘and they don’t even care, they’d rather blame it on someone else.’ That’s what many of the adults around me said. Not my parents, to be clear – we were raised in a household that strongly looked down on bigotry – but the sentiment was pretty much everywhere.

SWITZERLAND – JANUARY 01: MONTREUX ROCK FESTIVAL Photo of PUBLIC ENEMY, front L-R Flavor Flav, Chuck D, Professor Griff (Photo by Suzie Gibbons/Redferns)

Yes, people 20 years younger than me, it sounds quite like what critics now say about Black Lives Matter, despite … well shit, if I go into a BLM segue this piece will triple in size, and it’s already three times longer than I intended. Let’s just say I think much of the criticism is absurd if you read the actual platform put forth by the Black Lives Matters founders rather than the knee-jerk stuff pushed by fringe websites.

Anyway, the message of that Public Enemy video intrigued me. So did the music. I had grown up enjoying all the “safe” rap music white kids of the day liked. I knew the lyrics to UTFO’s “Roxanne, Roxanne” and the legendary “La Di Da Di.” I liked Run DMC and the Fat Boys. The most rebellious thing I knew was the Beastie Boys “Licensed to Ill,” which had taken my elementary school by storm with its talk of parties, girls, and (gasp!) getting loaded.

It all seemed pretty diverse for a little hick town in the sticks of New Jersey (and yes, people from outside the state, New Jersey does have sticks).

Public Enemy was nothing like that safe stuff. As I explored a little further, I heard horror movie music with lyrics about angry inmates tearing down the system (“Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos”), aggressive rave-ups that dropped unfamiliar names like Farrakhan alongside metal bands like Anthrax (“Bring the Noise”), and brag raps that had a political edge unlike the usual braggadocio of the day (“Rebel Without a Pause”).

What the hell was this, and why was it so awesome? I had no idea, but I was hooked.

“They wanted me for the army or whatever. Picture me given’ a damn, I said never”

The music was undoubtedly a part of the allure for me. Public Enemy is still a damn good hip hop band today, still putting out strong stuff – seriously, this shit is good as hell – but those first few records were in a world all their own. The trio of It Takes a Nation of Millions…, Fear of a Black Planet and Apocalypse ’91 is among the greatest 1-2-3’s in hip-hop history. They created sounds like nothing ever heard before, a mix of punk attitude and layered sonics and audio so dense you could spend a dozen listens unpeeling the layers. Even if you didn’t care about the lyrics, the actual SOUND was engrossing, a pretty big deal to someone like me who loves dense soundscapes.

There was something more than the total package, though. I think part of the allure was that it sometimes felt like I wasn’t supposed to be listening to this music. Like I was doing something I wasn’t supposed to. It was out there, anyone could listen to it, but it seemed clear to me that these guys didn’t give a shit if I listened to it.

And sometimes it was even a little scary. These guys were not afraid of being confrontational. Hot Press wrote back in 2000:

Chuck D and Flav’s redneck-baiting refrain of, “Elvis was a hero to most/But he never meant shit to me you see/Straight up racist that sucker was/Simple and plain/Motherfuck him and John Wayne” amounted to nothing less than an iconocataclysm: a blunt rebuttal of four decades of WASP hero worship, issued at earthquaking volume.

Listening to Public Enemy as a teen in my little white town of 3,000 was kind of weird. Rumors circulated among friends based on interpretations of their lyrics. One rumor suggested there was going to be a black uprising in 1995, hinted at in the lyrics. The group was part of a radical religious movement. And so on. It was ridiculous, but there was something in the back of my sheltered mind that wondered.

Other stuff didn’t seem as ridiculous. The band didn’t like white people. The FBI was monitoring them. Etc.

That was intriguing in an admittedly uncomfortable way.

Sometimes PE’s music made me feel unwelcome. It made no secret of making clear that it wasn’t for me. References to “devils” and the like made me wonder if I was part of the group they were so angry with – and the truth was, I didn’t know.

Yet here’s the thing: whether by design or simply a happy accident (I suspect a little of both), that feeling ended up being incredibly instructive. As a white kid living in a small town filled with other white kids and being immersed in a pop media that was almost all white, I never really knew what it felt like to not be spoken to in my entertainment. Everything spoke to me in some way. Movies, television, games, music, all of it was accessible to me by design, even so-called “black” music. All of it was made in a way that ensured it would not alienate me as an audience. It was done so in a way that was invisible to me, too. I didn’t notice things being twisted for my liking because as a young white dude who might have money one day, everything was made with me in mind. When the entire entertainment landscape is skewed that way, it’s really easy to not see it — and I didn’t.

Yet here’s the thing: whether by design or simply a happy accident (I suspect a little of both), that feeling ended up being incredibly instructive. As a white kid living in a small town filled with other white kids and being immersed in a pop media that was almost all white, I never really knew what it felt like to not be spoken to in my entertainment. Everything spoke to me in some way. Movies, television, games, music, all of it was accessible to me by design, even so-called “black” music. All of it was made in a way that ensured it would not alienate me as an audience. It was done so in a way that was invisible to me, too. I didn’t notice things being twisted for my liking because as a young white dude who might have money one day, everything was made with me in mind. When the entire entertainment landscape is skewed that way, it’s really easy to not see it — and I didn’t.

Think about the popular explosion of rap music during the 1980s and what dominated. Run DMC covering old glam rock songs. The Fat Boys doing riffs on the Beach Boys. Three Jewish punk rockers doing rebel rap.

Then comes along Chuck D and Public Enemy, who made it explicitly clear that while I was welcome to listen and learn, I wasn’t their intended audience. I could check it out if I wanted, but this shit wasn’t for me.

In other words, pretty much the same way generation after generation of black kids in America had felt when they watched a movie, saw a TV show, or listened to an album. They felt like an afterthought. Watch if you want, but this is for everyone else.

Chuck D pointed out in an interview with Spin, “Most black people, just to keep our heads over water, must know how the white structure operates, and we must know how our own structure operates. We have to know the white thing, because we’re getting it pumped to us daily – in the schools, on TV, and in the newspapers. But white Americans generally know little about how black Americans feel.”

He was right. Public Enemy’s music and message smacked me with that realization in a big way, and it’s something that has never left me.

“I got a right to be hostile, man, my people been persecuted.”

So here was this one thing that wasn’t for me. This thing that was not intended to appeal to me. A new and popular thing that came close to saying, “Nope, not for you, white kid! If you want to check it out, just listen and learn!”

Kind of off-putting, right? A little annoying?

Perhaps, sometimes flat-out YES, yet who was I to complain? Hell, I had a million other things that were for me I could turn to if I wanted to. Maybe it was because I felt challenged, but instead of being angry and frustrated that they didn’t tailor what they did for me the way every other pop entertainment thing did (or maybe it was because PE spoken to the anger and frustration teenage me felt at his place in the world), I accepted Chuck D’s invitation. I listened and tried to learn.

The things Public Enemy expressed were instructive. As a moody teenager, I knew about feeling isolated. About feeling like the “other” and feeling like it was me against the world. About feeling like forces were lined up against me. So there was a part of me that related to what Chuck talked about.

That was just moody teenager shit, though. You grow up and move on and become just another dude going about his business.

But what if you can’t erase all that? What if your “otherness” is an inherent part of you, etched onto your skin, and you’re reminded of it every single day you step outside and go to the grocery store or watch the news or get pulled over by the cops? What if there were forces lined up against you who saw you only for your outward appearance? How would that feel?

But what if you can’t erase all that? What if your “otherness” is an inherent part of you, etched onto your skin, and you’re reminded of it every single day you step outside and go to the grocery store or watch the news or get pulled over by the cops? What if there were forces lined up against you who saw you only for your outward appearance? How would that feel?

That sounded shitty. And the more I looked, the more I realized a lot of things sounded kind of shitty.

Public Enemy forced me to try on shoes I had never worn before. I could never truly understand, of course, not without actually living in black skin, but I could try to open my eyes a little. I could try to empathize in some way and recognize that all things equal except the color of our skin, a black male of the same age, income level, and education as me will still have had a much different experience as an American than I. That’s not always a comfortable reality to accept, but it’s also one that can’t be ignored.

Getting pulled over by the police is a different experience for me than it is for a young black man. Despite what head-in-the-sand types want to believe, that’s just a fact. If I get caught with pot, I get a fine. If a young black man gets caught with pot, they go to jail. If a black man and I are both sentenced for the same crime, he’ll get a harsher punishment than I will. And on and on and on. In fact, just about every phase of the justice system shows racial disparities, and the so-called War on Drugs in particular has done devastating damage to black social mobility.

Some people dismiss the notion of systemic racism as manufactured bullshit, but there are a few salient points to consider:

- According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, drivers of all races are stopped at similar rates, but black drivers are three times more likely to be search. (Source)

- According to the National Research Council, drug arrest rates are higher for blacks, even though blacks and whites use drugs at about the same rates. (Source)

- In Ferguson, a city in the news recently for its racial strife, 7 percent of whites who got pulled over were searched, resulting in contraband 34 percent of the time, while 12 percent of blacks who got pulled over were searched, resulting in contraband 22 percent of the time – less than whites! (Source)

- Criminology suggests that habitual offender laws are more often used against blacks than whites, even when they could be applied to both, and when being brought up on charges for similar crimes, prosecutors tend to seek harsher charges on blacks than on whites. (Source)

- Another study showed that even with similar criminal histories, blacks get longer sentences than their white counterparts. (Source)

- And those cries of “why don’t they ever talk about black-on-black crime?” Setting aside the fact that black groups do, regularly and daily — that could be the subject of an article all its own — it turns out white-on-white murder rates are about the same as black-on-black murder rates, 82.4% to 90%. So, basically just a shitty distraction argument offered by people who don’t want to acknowledge that systemic racism exists. (Source)

These are things I probably wouldn’t have given much thought to prior to Public Enemy helping open my eyes to the frustration felt by young black men in a system that often seems designed to work against them, in part because these things rarely have a direct impact on my life — and yes, there is a term for that, and yes, you know what it is. I knew that racism was a thing, sure, and was raised to see it as wrong, but I hadn’t given any deep thought to what it meant to be on the other side of it. Not the name-calling part that we all agree is wrong, but the deep seeded, inescapable part woven into the fabric of America.

Look at the aforementioned “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos.” It appears on the surface to be a tough guy fantasy about fucking up The Man, but look closer and you see that it’s a parable about how the disenfranchised and dehumanized are left to either rot in their circumstances or tear down the system that has been designed to work against them. This is something difficult for most of us to relate to, which is why it’s so easy to see the imaginary violence instead of the political message behind it:

Even “soft bigotry” is something I’ll never really have to deal with. If I say something smart – fat chance of that! – no one is going to comment that I am a “well spoken young man.” And no, that’s not actually a compliment, it’s 1) condescending as hell, and 2) the idea that blacks typically aren’t well spoken is implicit in the statement, which makes it, you know…

Plus, I’m never the token friend. I always get to be treated as a person first and an Insert Color Here person second rather than the other way around. I haven’t been eyed up in a store since I was 19. And on and on.

At worst, I was called a “spic” as a kid because of my last name, and a few times shortly after 9/11, I was harassed after growing out a full beard by people who thought I was Middle Eastern, including getting followed to my house. Thing is, those things couldn’t have a lasting impact on me, because at the end of the day I am what I am: a middle class white dude in America living in the suburbs. This country is built for me.

Without using the terms we use today, Public Enemy made me aware of “othering,” of white privilege, of systemic racism, and in my mind the most important thing of all, of why many blacks are frustrated with the system and want to see major change in our country. They made me understand that the well-intentioned idea of being “colorblind” is actually kind of insulting, since it completely ignores the realities of what it means to be black in America today – and you can’t fix the inequities in the system until you recognize that YES, we DO have different experiences depending on our race. After all, black people don’t get to pretend they’re not black. It’s their daily reality and impacts every aspect of their life. By deciding that I’m “colorblind” — and yes, at one time I did proudly make such declarations — I’m essentially telling friends and acquaintances of color that a huge, huge part of who they are doesn’t matter to me and that I’m going to refuse to acknowledge how it shaped them.

This is a message that even 30 years after their debut still needs to be delivered loud and clear. In a lot of ways, these are all hard realities to take in, to understand, and to accept as valid when so much of it can not and does not touch your life (read: my life) in a tangible way. Acknowledging that life differs for you in America depending on your race takes work, and it’s work that doesn’t always feel good. It means going to a place that can be pretty uncomfortable.

But Public Enemy doesn’t give a shit whether or not you’re uncomfortable, as long as you’re along for the ride.

“When I get mad I put it down on a pad, give you something that you never had”

A few weeks ago, I’m in the car with my wife when I put on some tunes. I was feeling some Fear of a Black Planet, and jammed it fairly loud when this came on:

When the song was over, she asked, “What year did this come out?”

“1990, I think.”

“Really?”

“Yeah, why?”

“They were ahead of their time with this subject, weren’t they?”

They were … sort of. More accurate to say that in the quarter of a frickin’ century since this song came out, not much has changed. How sad is that? While we have made some strong progress on this front – see the awesome Luke Cage or the strong black women at the front of shows like Scandal and How to Get Away With Murder – Big Daddy Kane’s verse is not only one of my favorite verses in hip hop history, most of it still resonates:

As I walk the streets of Hollywood Boulevard

Thinkin’ how hard it was to those that starred

In the movies portraying the roles

Of butlers and maids, slaves and hoes

Many intelligent black men seem to look uncivilized

When on the screen

Like a guess I figure you to play some jigaboo

On the plantation, what else can a nigga do?

Those lines struck me then, but they strike me harder now. They strike harder now not because we haven’t made any progress in the things Kane was calling out – I think it’s undeniable that we have, even if the magical negro still seems to be Hollywood’s favorite way to break the “thug” stereotype it perpetuated for so long, and even if cultural whitewashing is still par for the course – but because that progress now routinely causes a backlash among white people who don’t like seeing their world colorized.

That’s frustrating to me. My entire life, almost all of pop culture has been geared towards me. I don’t have to look hard to find characters I can relate to or who reflect me in some way, because as a straight white dude I am frickin everywhere. And no, that’s not a complaint, nor is it me expressing guilt. It’s just me expressing a fact. When it comes to popular entertainment in America, I am the default setting. (Quick segue: Louis CK has a funny take on this.) Pop entertainment is easy for me because it’s built for me.

So what’s the big deal if people of color get more roles? Are featured more often in movies, in books, in TV shows? Why shouldn’t they have the privilege of seeing themselves reflected in their entertainment, too, and in a way that isn’t an exception or a novelty or that is about being Different? How on Earth does that worsen my life in any way? It doesn’t. It actually does the opposite: it enriches my life in ways that deserve an essay of its own.

Yet when diversity in entertainment becomes noticeable, you can bet that a bunch of people will be up in arms about it. It’s being “shoved down our throats” or we’re seeing “diversity for the sake of diversity” and other such nonsense, as if seeing more prominent black roles is somehow an attack on white people. That’s just silly.

The question is, would I have ever seen or noticed this had Public Enemy not brought it to my attention? Perhaps. I like to think that my character is decent enough so that I’d have come around on my own. At the very least, though, Public Enemy nudged me down a path that encouraged empathy, understanding, education, and recognizing differing experiences. The journey down that path never really ends, the list of what I don’t know seems to be (and surely is) endless, but I’m glad to be wandering down that road nonetheless.

“Some devils prevent this from being known”

It wasn’t all pure and clean, of course. There were touches of homophobia in some of their lyrics, notably in “Meet the G that Killed Me”. (Chuck has since come out in support of gay marriage.) The group almost fell apart after anti-Semitic comments by original member Professor Griff, which included the statement, “Jews are responsible for the majority of wickedness in the world.” (In his 2009 book, Analytixz, Griff moved away from this stance, saying his comments were “not correct” and said he was “not the best knower,” a humble nod to the ignorance we all succumb to from time to time.) They’ve defended Louis Farrakhan (sorry, guys, in my eyes but the guy is unquestionably a bigot) and one of their best songs, Welcome to the Terrordome, arguably contained thinly-veiled anti-Semitism.

Then you have the following video, made in response to Arizona’s refusal to make Martin Luther King. Jr. Day a holiday, which created a firestorm of controversy for seeming to endorse political assassination. The song is fucking awesome, and Chuck still stands behind his protest song and video – and I don’t disagree with him on that, even if I DO disagree with the idea of violence — but it’s not hard to see why some said it went a step too far:

You can’t really be a brash protest group without making some waves and saying some shit you shouldn’t say, I suppose. Sometimes free speech hurts. And it should.

All of the above underscores the idea that P.E. is not free of fault or sin. They’ve occasionally been on the wrong side of bias as well. They’re humans, and like anyone else, they’ve been capable of making me uncomfortable for the wrong reasons. I love their music and love their potency, but that doesn’t mean I stand with everything last thing they say in their music or in interviews, nor do I think they’d want me to. They’d want me to listen, think and form my own conclusions.

I also learned much later in life that some of what I saw and interpreted in the band wasn’t quite accurate. I initially thought Public Enemy’s work wasn’t aimed at me, yet they would go on to work more closely with white musicians than perhaps any hip-hop act in history. This is a band that opened for U-frickin’-2, ferchristsake! It really doesn’t get much bigger than that. Look at their crowds these days, and they are mostly white. An unusual situation for a band so known for their uncompromising blackness, but the band sees this as a way to spread an important message to people who need to hear it.

I had misinterpreted their goals, too, and recognizing that meant their message resonated in new ways even decades after first hearing their music. Dropping names who had been (or allegedly been) associated with anti-white sentiment, such as Louis Farrakhan and Elijah Muhammad, made it seem as if the band had an antagonistic bent – and they did, but it was antagonistic towards corrupt systems, not towards white people. Huge difference.

They came out in paramilitary gear and used confrontational imagery, but as Professor Griff explained in a 2000 interview, “For whitebread America to see organized black men, of course it struck fear. But our main target wasn’t to destroy whitebread America, it was to destroy the niggardliness in black people, get them to stand up and be real men and women.” When Griff complains about dealers “selling drugs to the brother man instead of the other man” in Night of the Living Baseheads, he’s not urging dealers to go ruin the lives of non-blacks, he’s pointing out to these dealers that they are ruining their own community. The difference between these two messages is subtle and easy to misinterpret, but it’s important to see.

In a later interview, Chuck D expanded on his views on race and politics: “I think people are people and human beings are human beings. I look at myself as being a citizen of the world and I think art and music bring human beings together, John. But, I also think governments have always had a historical tendency to split people up, categorize them, and put them in compartments.”

In a later interview, Chuck D expanded on his views on race and politics: “I think people are people and human beings are human beings. I look at myself as being a citizen of the world and I think art and music bring human beings together, John. But, I also think governments have always had a historical tendency to split people up, categorize them, and put them in compartments.”

The lesson here? Dig deeper. If someone is presenting you with an image that seems confrontational or off-putting, ask why and try to figure out the purpose of that image, not to mention why the image makes you uncomfortable in the first place – and yes, that might mean confronting inner biases you’d rather not admit to. We all have them. The question is, are we strong enough to face them and acknowledge them for what they are?

Lessons like that are a huge reason why Public Enemy remain important to me.

I got a different view of who these people were off stage, too. In the interest of privacy I’ll keep this vague and brief, but the story is worth mentioning even if I can’t get too specific. I had the pleasure of briefly getting to know one of the founding members of the band, albeit from a distance. They heard about my fandom through a mutual connection and reached out to me. This mutual connection had only the vaguest idea what Public Enemy was; they knew the band member out in the “real” world, not as music stars. When told I was a fan, the band member showed genuine interest. He’d ask our mutual connection how I was doing when they saw one another, and our mutual connection shared with me what a kind and humble person this guy was. On multiple occasions, he sent me stuff in the mail – signed CDs, DVDs, books, PE memorabilia, that sort of thing. Why did he do it? Just because. No other reason than to be generous.

All of this was in stark contrast to the image the media portrayed of this person. The media showed one thing, but what I experienced was a kind person who was grateful that people were interested in what he had to say. It further cemented the idea that I had been mistaken with my initial “this is not for me” impression, and that we ought to look twice when confronted with someone’s public image.

Twenty years after I had discovered them, Public Enemy was still opening my mind.

“Preach to teach to all, ‘Cause some they never had this”

So, Public Enemy changed the way I see the world. They didn’t turn me into a white hotep (is that even a thing?) or an activist or a white person who desperately longs to be accepted by black people or whatever. That’s not what this is about.

What they did do is get me to think about other experiences in a way I never had before, and to understand and respect the anger and frustration so many black people feel. Again, I can’t truly know what it’s like to walk in their shoes. That’s impossible. What I can do is try to listen, understand, and empathize. The band opened that door of thought and wouldn’t let me close it.

I don’t like to use the term “woke.” To me, there is a finality to the term that implies, “I’m here! I’ve arrived! Embrace me as part of the extended POC family because Now I Understand.” Life is not that simple. Neither is a complex issue like understanding what it means to live in someone else’s skin. And hell, I’m still just some goof from the Jersey ‘burbs pondering my next craft beer and what I should play on Xbox. How “woke” can I be? Not very. I still have a shitload to learn.

I also don’t refer to myself as an “ally” for similar reasons, and also because “ally” comes with implications that don’t work for me. First, it implies taking action, and you know what? I’m just some guy trying to pay the bills. I don’t get involved in a meaningful way and I don’t really take action on social issues, outside of talking about these topics with trusted friends, cutting shitty people out of my life, and occasionally getting sucked into Internet debates. Mostly I just do my own thing, as is my privilege. Posting a blog like this is not taking action, it’s just talk, and talk is cheap. Besides, “ally” kind of implies that people of color need me at their side. They don’t. What they need is for people like me to not be an obstacle anymore.

So I’m not “woke” or an “ally,” and would feel presumptuous as hell if I declared myself such. I’m just a dopey suburban dude trying to make sense of it all.

I do, however, hope I’m intelligent enough to understand that our experiences shape us and that I’m aware enough to listen to the experiences of those who don’t look like me. Colorblind? Screw that. Used to think that was noble. Now I recognize that it’s ignorant – not because it isn’t a nice pipe dream, I suppose, but because we sure as shit aren’t there yet and won’t be any time soon. We’ve got to acknowledge race if we’re going to build a better society.

I do, however, hope I’m intelligent enough to understand that our experiences shape us and that I’m aware enough to listen to the experiences of those who don’t look like me. Colorblind? Screw that. Used to think that was noble. Now I recognize that it’s ignorant – not because it isn’t a nice pipe dream, I suppose, but because we sure as shit aren’t there yet and won’t be any time soon. We’ve got to acknowledge race if we’re going to build a better society.

There is still a lot of shit I don’t know or understand, stuff I can’t relate to or don’t get, mistakes I’m going to make and bad assumptions I’m going to have. I’m simply doing my best to recognize how our experiences shape us and what that really means, knowing I’ll never fully get it.

But that’s okay. In part because of the impact Public Enemy had on me, I recognize that. Their message has been very consistent over the years, and it’s one I won’t soon let go of: Never stop learning.

Excellent read Eric San Juan! It brought out a lot of emotion and memories in me. I have some stories to tell you. Hopefully, we can all help change the world a little bit at a time.

Thank you! On one hand it’s just music, but to me there’s no such thing as “just music.”

The music tells a story and sometimes it’s an outlet for the frustration of trying to say something when so many are not really listening or understanding.

I think a couple of you wanted to see this when it was finished, but can’t remember all of you. I think it was Terry, Jeff, maybe Glenn? I might be misremembering. Matthew maybe, too.

Yep. It was me! Thanks!

On a sidebar….Did you see ‘Straight outta Compton’? Very enjoyable.

Not yet. It’s been in my queue for a while now. I’ve had some concerns about them allegedly softening some of their uglier behavior, but ultimately I’m going to see the damn thing regardless.

I am sure they did soften their behavior but the movie was really good anyway.

It’s great. Seen it thrice. It’s the shiznit

good shit

This is great, man.

Thanks. It was one of those things where in writing it I kept feeling like I was getting pulled down side paths, only to realize they weren’t side paths, it was the main fucking road

Half my stuff feels like that. You done good!

Dude. Very nicely done.

Thank you, sir, and I appreciate you sharing it. If the *only* thing that results is a few more people hear a PE song or two, I’ll be happy. If they actually get wrapped up in their words and music, all the better.

I’ve not got the time just at the minute to read all of this but I’ve got a fair way through. I’ll definitely finish it because I love them too. I think it’s because they represent the biggest cultural shock of our lifetimes, in many ways. They were sending out a message to teenage kids all over the world that cultures and nations are machines, machines designed to process people. The starkness of America being an “Anti-Nigger Machine”, as Chuck D sees it, DEMANDS that a moral human should look at why he feels that way and hey – guess what? He’s right. What I liked most about it was that he wasn’t giving in to any of their shit. My favourite bit of Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos, apart from the great line about his own government being suckers, is that he reassures us that he won’t be in their army (or whatever) and challenges us to picture him giving a damn. And he never has. A living legend.

The casual dismissiveness of that “or whatever” is as potent as anything you’ll find. Volumes are spoken with two seemingly throwaway words.

Well done! Enjoyed every minute!!

Kavon Shah

Pingback: Someone shot up my friend’s workplace – and it should scare you as much as it scared him – ERIC SAN JUAN

Pingback: What Is The Best Equipment For Listening To Hip-Hop? – ERIC SAN JUAN

Pingback: 28 Songs that Changed My Life: Public Enemy, “Night of the Living Baseheads” (1 of 28) – ERIC SAN JUAN