Eight years ago, Stephen Segal, then creative director at the legendary Weird Tales magazine, asked if he could use some modest writings I had been doing on Neil Gaiman’s Sandman for a 20th anniversary retrospective he was putting together. Naturally, I said yes. Sadly, the series was lost in a website revamp. Not wanting it to disappear into the ether, I’m now presenting it on my site in 11 parts (alas, without the benefit of Stephen’s editing; these are pre-publication versions). Hope you enjoy.

Recurring Dream: An Anniversary Re-reading of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman

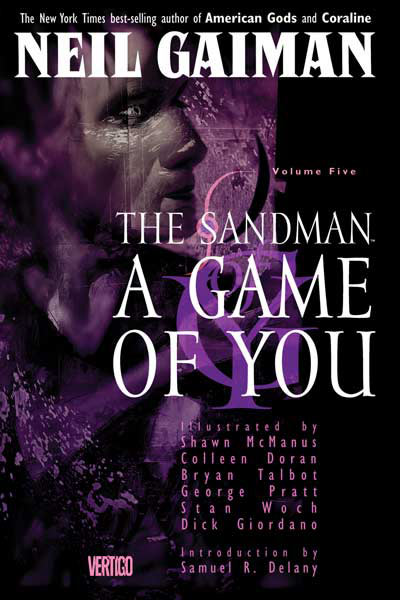

Part 6 of 11, A Game of You

Originally published on the Weird Tales website, January 2009

Small breasts. A seemingly minor thing, yet in reality rather important. But more on that later.

Small breasts. A seemingly minor thing, yet in reality rather important. But more on that later.

A Game of You was not my favorite story arc when I first read Sandman, nor does it leap to the front of the pack here, re-reading it many years later. Oh, it’s a fine story, a kind of nightmarish fairy tale plucked from the things we leave behind in childhood and draped in the garb of a directionless adult who doesn’t know what she wants to be. But it doesn’t sing to me the way the vast majority of Neil Gaiman’s 2,000-page epic does.

Not that there isn’t a lot to like here. There is. A Game of You focuses on Barbie, the painfully plastic blonde from The Doll’s House. She left Ken and now lives in an apartment building populated by an assortment of semi-misfits. Sound familiar? Yes, we walked this ground a few story arcs ago, but the approach is much different. Further, to cement the idea that nothing exists in a vacuum in Sandman, some of these characters also have ties to Preludes and Nocturnes, specifically the young lady featured in the episode inside the diner. The references are fleeting and subtle – one of Gaiman’s great strengths is trusting the reader to put the pieces of his puzzles together – but they serve to connect this vast world of seemingly disjointed stories.

And playing with childhood toys in an adult, often sinister way? Sure, it’s been done before, yet few have managed to make it seem perfectly sensible.

So if this is the one arc that doesn’t speak to me on the same level as, say, Brief Lives, I beg your forgiveness. It’s not a matter of not recognizing its strengths, it’s simply one of taste. We spend six issues in this world when it feels like three or four would have better suited the story. We’re not nearly as invested in Barbie as we are the other tenants, so our time with her seems overlong. Once the initial oddness of the fairy tale characters wears off (this by the end of the first issue), so, too, does the novelty. The story overstays its welcome.

That said, small breasts.

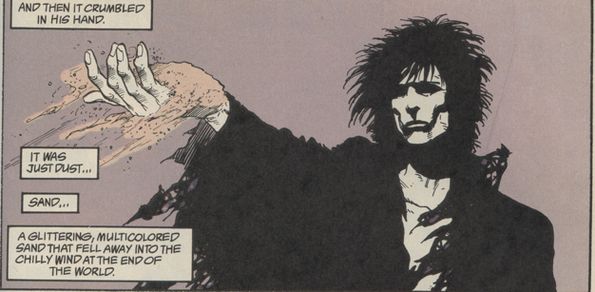

No, I’m not having a fit of Tourette’s here. One of the most noteworthy achievements of Gaiman’s Sandman was crossing the gender line. Comic books are a medium decidedly dominated by males. Over the years the adolescent power fantasies of superhero comics all but bullied other genres out of the mix, leaving caped, muscle-bound men and empty-headed, big-breasted women to rule the roost. (Yes, the real history of American comics is more complex than that, especially the impact Seduction of the Innocent had on the popular medium, but for simplicity’s sake the point stands.) These days the rise of graphic novels and concerted efforts by some publishers, not to mention the popularity of manga, has meant growth in female readership, yet even with this in mind comics remain a boy’s playground.

In 1989, when The Sandman first began publication? Forget about it. Women were nowhere to be seen.

But Sandman did a lot to chip away at the testosterone wall built between women and comics. I say “small breasts” half jokingly, but really they’re symbolic of something Gaiman tapped into. Women were not fantasies. They weren’t models or hourglasses or one-dimensional stereotypes. I mean, let’s face it, most comic book writers can’t write nuanced, believable human beings, much less nuanced, believable women.

So here comes Gaiman and his cast of female characters. Instead of being variations on the same theme with “femme fatale” the extent of his ability to write complex women, they’re real people with real depth and real character and real thoughts, feelings and emotion. Comics, being the visual (and historically shallow) medium they often are, draw our attention to how things look. Thus, the small breasts we see here. These women are sometimes chubby and frumpy, and sometimes thin and flat-chested, and sometimes awkward and unattractive, and yes, sometimes quite gorgeous.

In other words, they’re women. They’re people as varied and different as you and I. None of these factors are special story elements shoved in our face with clumsy, “Look, I’m writing normal people! Isn’t that clever and open-minded of me?” writing, they just … are.

It’s hard to overestimate how big a factor this was in Sandman’s wide appeal and longevity. My wife devoured it. Many wives and girlfriends devoured it. Sandman proved to many people that comics did not have to be adolescent power trips; that they could feature characters – female characters – as complex and real as any work of literature. We longtime comic readers may have suspected this all along, but the general public didn’t. For most, comics were disposable rubbish with the worst sort of one-dimensional characters, ESPECIALLY with regard to women. Along with some other notable works, Sandman kicked at those barriers. A Game of You is a good example of how and why.

No, it’s not my favorite story arc in the series, but when a series features material as strong as Season of Mists, Brief Lives and World’s End, that’s hardly an insult. And yeah, favorite or not, there is obviously a broader message to take from this arc, and a pretty important message at that.

I feel very much the same as you about this story – could have been shorter. But miles ahead of most of the other comics offered at the time.

By the way, when I am done rereading some of my Valiant stuff I will be tackling Sandman again – first time in about 5 years.

It was just so refreshing to see these characters treated as real and distinct individuals rather than the 2 or 3 female stereotypes that dominated most comics. I don’t think I knew WHY it seemed so different at the time — I guess I was around 20 or so and didn’t think much about these things — but subconsciously, it resonated as being something outside the comic norm.