Eight years ago, Stephen Segal, then creative director at the legendary Weird Tales magazine, asked if he could use some modest writings I had been doing on Neil Gaiman’s Sandman for a 20th anniversary retrospective he was putting together. Naturally, I said yes. Sadly, the series was lost in a website revamp. Not wanting it to disappear into the ether, I’m now presenting it on my site in 11 parts (alas, without the benefit of Stephen’s editing; these are pre-publication versions). Hope you enjoy.

Recurring Dream: An Anniversary Re-reading of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman

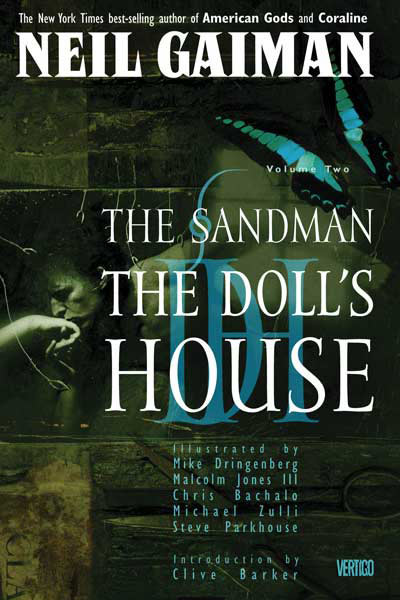

Part 3 of 11, The Doll’s House

Originally published on the Weird Tales website, January 2009

The Doll’s House picks up seemingly throwaway threads from Preludes and Nocturnes and creates story out of them. Builds mythology from stuff that appeared to be mere tone and atmosphere building.

The Doll’s House picks up seemingly throwaway threads from Preludes and Nocturnes and creates story out of them. Builds mythology from stuff that appeared to be mere tone and atmosphere building.

This is what Gaiman does. This is what Sandman is. And even at this early stage, when he’s still getting a feel for the world he’s creating, it’s brilliant.

When we caught glimpses of troubled sleepers and people struck into dreaming comas in the first story arc, it appeared to be little more than attempts to vividly paint the impact of Dream’s captivity. Gaiman was showing us a world without Morpheus, telling us why he is important and using a series of tiny arcs to do it. We saw people caught in an endless slumber, a woman tragically raped while in a coma, a man destined for insanity, and more. These were passing references to a slew of people, unimportant to the main story save for adding texture to it. Just the stuff of atmosphere building. Or so it seemed.

But we were wrong. One of those little “atmosphere” arcs becomes central to The Doll’s House.

We begin with a prologue that feels as if it’s a standalone story, something largely unrelated to the whole. This is an illusion, of course. Nothing in Sandman exists in a vacuum. Throughout the series Gaiman proved to be a master of using even the smallest of story elements and passing references as springboards to larger tales. I’m not talking clunky comic book stuff, either, those “gotcha!” revelations or explanations of what happened between panels and the like. Gaiman is not so clumsy as that. Here we’ve got the sense that a mythology is being built. Not a make-it-up-as-you-go-along mythology. A real, true, coherent, densely interwoven mythology.

For instance, this prologue, “Tales in the Sand,” appears to be the story behind a brief encounter Dream had while in Hell shown in the first volume. It was nothing more than a brief interaction with a lover who allegedly wronged our protagonist, a hint at something in Dream’s past. In “Tales in the Sand” we learn this lover’s tale and why she is in Hell. It seems like this prologue is unconnected to The Doll’s House, but what we don’t realize is that this story will also serve as the roots for one of the most important arcs of the entire series, the forthcoming Season of Mists.

Are you sensing a pattern here?

Anyway, The Doll’s House. You can feel Gaiman starting to shake the Alan Moore dust off his bones with this arc, breaking free from his mentor’s influence and juuust starting to create his own voice. (It’s not stretch to call Moore Gaiman’s mentor. It was Moore, after all, who showed Gaiman how to write a comic script.) The influence is still there in the way Gaiman handles his serial killers and in the lyrically self-aware narration, but it’s a big step forward from the very Moore Preludes & Nocturnes.

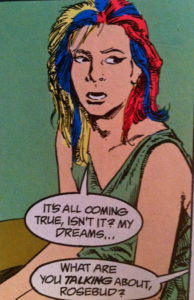

Gaiman shows himself to be adept at creating strange, surreal characters here – and I don’t mean the serial killers! Rose’s roommates are an odd but interesting and likeable bunch. And yeah, those serial killers are well realized, too. He has a knack for establishing character without having to use a lot of strokes. Any one of these side figures could probably sustain a story in their own right.

We also see some playing with the comic form. Nothing groundbreaking, but stuff that keeps us on our toes. Typewritten letters as narration; lettering being used in creative ways; pages being turned on their side to represent Rose being turned on her side (figuratively, not literally); a twisted dream sequence that puts us into the psych of her roommates.

Lots and lots of good stuff.

There is an interlude here about 3/5 of the way through the arc, “Men of Good Fortune,” that I can’t help but think should have been moved to Dream County in the collected editions. It’s a standalone story (but as always, not really), albeit a very good one, and feels out of place in the midst of this extended arc. Why not collected with the volume that’s all about standalone stories?

(Of course, it’s worth noting once again that in Sandman even a standalone story is not as standalone as you think. Characters, people, places and events can still touch other tales. This “standalone” tale, for instance, is extended in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and a part of it comes up in Season of Mists. Let it be a lesson learned: Take nothing in Sandman for granted.)

The arc wraps up with a satisfying resolution that never feels cheap and leaves us without any doubt: We’re reading the start of something special.

The astonishing thing is, Gaiman isn’t even there yet. He’s not yet firing on all cylinders. With this arc, he’s still working to move away from his influences and to find his own voice. And yet it’s really quite good. Not yet UTTERLY BRILLIANT, as this series will soon become, but quite good indeed.

Pingback: Looking back at Neil Gaiman’s Sandman 28 years later – part 1 of 11 – ERIC SAN JUAN