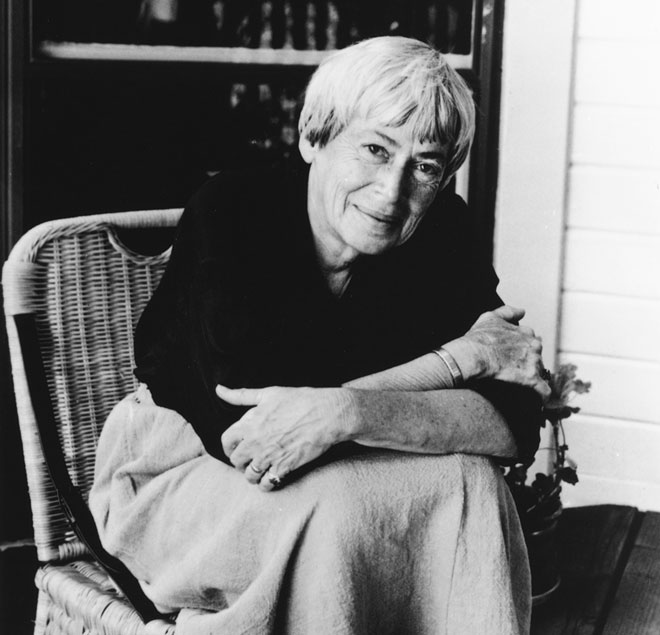

As I write this, the news is breaking that Ursula Le Guin, one of the 20th Century’s great novelists, has passed away at 88. She was a giant, known for her work in science fiction yet crafting works that transcended the genre. Whenever I’ve thought of the authors who have inspired me, awed me, impressed me, humbled me, shaped my tastes, molded my views, and made me see the power of the genre, she was always on the short list.

As I write this, the news is breaking that Ursula Le Guin, one of the 20th Century’s great novelists, has passed away at 88. She was a giant, known for her work in science fiction yet crafting works that transcended the genre. Whenever I’ve thought of the authors who have inspired me, awed me, impressed me, humbled me, shaped my tastes, molded my views, and made me see the power of the genre, she was always on the short list.

It wasn’t the awards that made Le Guin great, though she got gobs of them. It wasn’t even that her stories were entertaining, though they were. It’s that she reinterpreted the world, showing us both how it truly is (even when we didn’t acknowledge it) and how it could be (both good and bad).

Like many, I discovered her work through the Earthsea books, her series of young adult fantasy novels. I read them out of order, first reading The Farthest Shore, the third book in the initial trilogy. For a book supposedly aimed at younger readers, it was a heady, meditative examination of mortality, death, rebirth, and the idea of balance in all things. It was probably my first experience with Taoism, though I didn’t realize it at the time. As a younger reader, I just thought it was a weirdly moody fantasy novel that turned its head on traditional fantasy tropes. (And yes, it’s that, too.) Rereading it multiple times over the years revealed depths I hadn’t first seen about this ancient Chinese practice. Notions of balance, of all of us being part of something greater than ourselves, of a cycle that continues with or without us, these all turned the typical fantasy idea of One Long Hero Impacting The World on its head. I eagerly sought out the other books in the series. And yes, all are wonderful.

Over the years, her works continued to challenge me.

In The Telling, she explored the power of storytelling and oral traditions, confronted religious fundamentalism and fascism, and celebrated the heroism behind doing something as simple as speaking. That’s a message that resonated with me in a big way. The freedom to speak and the oppressive weight of censorship, especially censorship drive by religious and political extremism, has been a sore spot for me since I was a child.

The Lathe of Heaven took a tired old trope — “be careful what you wish for” — and turned it into a meditation on good intentions gone awry, the secret lust for control in all of us, and how simple solutions to complex social problems only serve to create more problems. It’s a fantastical tale, one that blends Philip K. Dick (another favorite) with Eastern philosophy, and like most of her work, one that forces you to re-think the way you see the world.

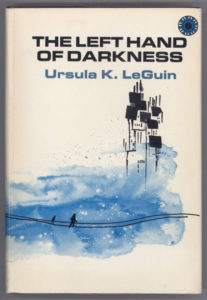

Many other wonderful books helped guide me along the personal philosophical journey I was already on — The Dispossessed, The Other Wind, and others — but perhaps the one that had the farthest reaching effect on me was The Left Hand of Darkness. This 1969 novel (and it’s remarkable to think of this having been written in 1969) was probably my first exposure to ideas that challenged mainstream notions of gender and sexuality. Genly Ai, the protagonist and essentially the stand-in for us, the readers, must come to understand a society without gender as we know it. Her goal was to imagine a society stripped of gender and to explore what that society would look like. At the time, it seemed like a pretty abstract concept. Still, as someone who already felt disconnected from the most boorish aspects of being a guy in the west, The Left Hand of Darkness didn’t merely reinforce my belief that uber machismo was pretty silly and off-putting, it shattered it into a million pieces. It forced me to take that fairly common feeling of having little connection to the chest-thumping American boys are (or were) raised to believe was how we should be and push the “what if” far further than I had imagined you ever could. It wasn’t merely a novel that asked for open-mindedness when it came to sexuality. It was a novel that asked us to re-think the very idea of what we all are. It was and remains a profound and challenging novel.

Many other wonderful books helped guide me along the personal philosophical journey I was already on — The Dispossessed, The Other Wind, and others — but perhaps the one that had the farthest reaching effect on me was The Left Hand of Darkness. This 1969 novel (and it’s remarkable to think of this having been written in 1969) was probably my first exposure to ideas that challenged mainstream notions of gender and sexuality. Genly Ai, the protagonist and essentially the stand-in for us, the readers, must come to understand a society without gender as we know it. Her goal was to imagine a society stripped of gender and to explore what that society would look like. At the time, it seemed like a pretty abstract concept. Still, as someone who already felt disconnected from the most boorish aspects of being a guy in the west, The Left Hand of Darkness didn’t merely reinforce my belief that uber machismo was pretty silly and off-putting, it shattered it into a million pieces. It forced me to take that fairly common feeling of having little connection to the chest-thumping American boys are (or were) raised to believe was how we should be and push the “what if” far further than I had imagined you ever could. It wasn’t merely a novel that asked for open-mindedness when it came to sexuality. It was a novel that asked us to re-think the very idea of what we all are. It was and remains a profound and challenging novel.

And that’s what science fiction does best. It challenges us.

She grew up in a household of anthropologists and was deeply interested in how human society worked. Not just our society, but all societies.– and for those of us in the west, where we believe ours is the One And True Way, that’s powerful.

Le Guin rejected the idea of being “just” a science fiction author, of course. She preferred to just be known as a novelist. Much like Kurt Vonnegut or Ray Bradbury, she transcended the genre. Sure, there were other planets and alien races and all the other trappings of the genre, but her work often wasn’t about that. Like the best science fiction, it was actually about us. Every time I read one of her works, I was left with more than just a feeling of having been entertained — and make no mistake, even just being entertained is a welcome thing. But her work went beyond that. With every book, I was left with a profound need to think about what I just read, to unpeel it, to wonder how its ideas and concepts fit into the way I saw the world. Her work extended beyond the page and reached out into the real world, kicking down barriers in thought and belief and forcing me to consider other ways of seeing the society I lived in.

Great authors can challenge you. Shake you. Change you.

And Ursula Le Guin was one of the greatest.

Goodbye, Ursula. You will be missed.

Great Eric!